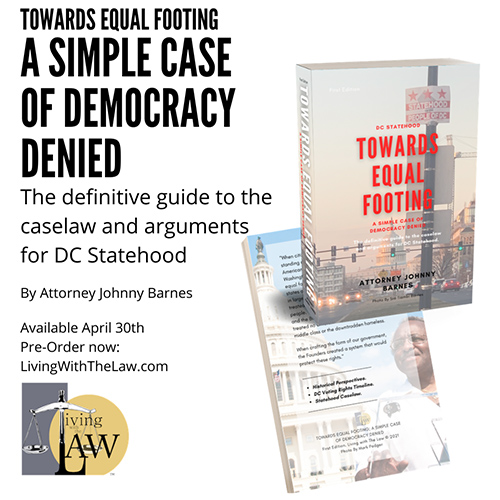

Book Excerpt: Towards Equal Footing

Towards Equal Footing: A Simple Case of Democracy Denied This 200 plus Page Book is the result of a half Century of research and study. It debunks the arguments of those who would try to use the Constitution to deny D.C. Citizens the very rights they demand for themselves. View an excerpt.

$51.00. Five dollars of the proceeds will be donated, equally to the ACLU and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. |

An Excerpt from Towards Equal Footing: A Simple Case of Democracy Denied

THE 23RD AMENDMENT IS NOT A BARRIER TO D.C. STATEHOOD

The Constitution gives rights. It does not take rights away. Yet, in its December Issue, the Washingtonian Magazine suggests that the 23rd Amendment could be a barrier to D.C. Statehood, "Would DC Statehood Also Give the Trumps Three Electoral Votes?" Borrowing from a long debunked Republican argument, the Magazine ignores that there is "Dead Letter" language in the U.S. Constitution, drawn from the Fugitive Slave Act that allows Masters to cross state lines to retrieve runaway slaves --- yes, still in the Constitution --- and argues that if we become a state, the 23rd Amendment would have to be repealed. PoppyCock. If we are forced to repeal the 23rd Amendment we won't become a state. The Republicans control enough State Houses to block any proposed Amendment to the U.S. Constitution; witness the Equal Rights Amendment for Women. They effectively have a Veto. I wrote to the Washingtonian to bring this flawed logic, addressed over the years by many Constitutional Scholars, and was ignored.

A reference to slavery in the Constitution is found in Article IV, Section 2. This is the fugitive-slave clause which reads:

"No Person held to Service or Labour in one State, under the Laws thereof, escaping into another, shall, in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom Service or Labour may be due." It is still there. Yet those who would be slave owners in 2020, like Trump and Mitch McConnell, would have us believe that the Fugitive Slave Act can just sit there, but the 23rd Amendment can not. Poppy Cock.

The Trump/ McConnell position has been addressed through multitudinous testimony by legal scholars on this issue, Democrats and Republicans in Hearings before the former House District of Columbia Committee, especially those during my tenure. Professor Viet Dinh, for example, who wrote the Evil Patriots Act while at the Justice Department. You may also find compelling the Testimony of Rock-Rib, Card Carrying Republican Charles Alan Wright, now deceased, President Reagan's lawyer, a former University of Texas Law Professor and Author of Wright on Federal Courts and Federal Systems, a treatise that all lawyers-in-training once read, including me in Civil Procedure Classes while in law school.

Does the Presence of the Twenty-third Amendment Preclude the Admission of New Columbia as a State?

In 1961 the Twenty-third Amendment[1] was ratified and added to the Constitution. Realigning the framework of the Electoral College, the Twenty-third Amendment grants to the District of Columbia a number of electors equal to what it would have if it were considered a state for purposes of representation (but never more than the least populous state). Opponents to statehood for the District of Columbia argue that the creation of New Columbia cannot occur through simple legislation and argue that the Twenty-third Amendment supports this view for two reasons. First, the very existence of the Twenty-Third Amendment demonstrates that any allocation of representation for the District has historically required a constitutional amendment.[2] Second, shrinking the District without repealing the Twenty-third Amendment would reward the few remaining residents of the National Capital Service Area with three electoral votes, a constitutionally unacceptable result.[3] Contrary to these arguments, the decision to admit New Columbia as a state would neither violate the Constitution nor trigger any constitutional calamities. Based upon the language of the Twenty-third Amendment and other relevant portions of the Constitution, statehood for District residents can occur through simple legislation. Repealing the Twenty-third Amendment is simply unnecessary.[4]

An analysis of the significant differences between Congressional representation and representation in the Electoral College illustrates that a constitutional amendment is not necessary to provide District residents with statehood, even though a constitutional amendment was used to provide District residents with electors in the Electoral College. In the Constitution, provisions related to the “seat of government” are discussed in Article I, while provisions related to electors are discussed in Article II.[5] Article I demonstrates a great deference to Congress by endowing the legislative branch with sweeping authority to “make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution” its various powers.[6] Among these powers is an “exclusive” authority over the seat of government, which the District Clause describes in similarly sweeping language. Many would argue that this power could be used to grant the District of Columbia representation in Congress even without the creation of a new state. Article II represents the other extreme. Although Congress may determine the day on which the Electoral College votes,[7] the Constitution does not provide Congress with any other authority to manage this process. Instead, the election of the President and Vice-President is precisely detailed and clearly unalterable by simple legislation.

Because the provisions concerning the Electoral College are found within the highly constrictive Article II, and because legislating with respect to the Electoral College is outside the boundaries of Congress’ broader Article I authority, granting District residents the right to vote (while remaining a district and not a state)[8] in presidential elections could not be achieved through statute.[9] Therefore, only a constitutional amendment could provide District residents with the necessary electors. Statehood, however, may be granted through statute because the Constitution specifically allows Congress to admit new states.[10] The creation of New Columbia and the shrinking of the district implicates Article I powers, which not only allow Congress to legislate in manners deemed “necessary and proper” for the United States in general, but also allows Congress to legislate in “all Cases whatsoever” for the district in particular.[11] This broad authority and explicit deference to the legislative branch indicate that Congress can provide the District of Columbia with statehood. Representation in the Electoral College is not similar to representation in Congress in this respect. The mere existence of the Twenty-third Amendment does not suggest that statehood can only occur through a change in the Constitution.

Opponents of statehood further argue that the creation of New Columbia would necessitate a repeal of the Twenty-third Amendment because the provisions entitle the few remaining residents of the National Capital Service Area to three electoral votes.[12] These residents would consequently be endowed with substantially more influence in elections for President and Vice-President, in violation of the principle of equal representation.

However, the purpose of the Twenty-third Amendment could still be achieved without endangering the rights of other citizens or altering the Constitution. Stephen Saltzburgh, a Professor of Constitutional Law from the University of Virginia Law School, describes the issue of the Twenty-third Amendment with tongue-in-cheek simplicity. Saltzburgh writes, “[t]he truth is, I don’t know why anybody cares about what happens with the Twenty-third Amendment…every time you tinker with the Constitution it’s so costly it would be better to leave it alone.”[13]

The challenge of the Twenty-third Amendment, though, proves slightly more complicated than Saltzburgh might hope. Although Congress can constitutionally reduce the District to only the federal buildings, some former residents of the District of Columbia would inevitably live within the geographical boundaries of the National Capital Service Area.[14] The residents of the White House, the homeless, and some military personnel would remain in the area. Denying these people representation in the Electoral College, representation which is explicitly guaranteed by the Twenty-third Amendment, could result in a clear violation of constitutional rights. The language of the Twenty-third Amendment provides the solution for statehood proponents.

Congress cannot pass legislation that would conflict with the Constitution. However, the creation of New Columbia would not be incompatible with the purpose of the Twenty-third Amendment.[15] Congress intended the Twenty-third Amendment to “provide the citizens of the District of Columbia with appropriate rights of voting in national elections for President and Vice-President of the United States.”[16] Under the proposed plan for statehood, the few remaining residents of the National Capital Service Area would vote as residents of New Columbia.[17] The people of the National Capital Service Area would therefore still receive the representation in the Electoral College that the writers of the Twenty-third Amendment sought to achieve. As Peter Raven-Hansen, a Professor at George Washington School of Law, so aptly states, “[w]hile no constitutional provision should ordinarily be read to yield a nullity, neither should any be read to yield an absurdity.”[18] The Twenty-third Amendment was never meant to provide a handful of people with disproportionate influence in the electoral process.

With the creation of New Columbia, the objective of the Twenty-third Amendment would be realized. Opponents of statehood remain uncomfortable with what they claim is Congress disregarding explicit constitutional requirements. That is no more the case here than in many instances of other Constitutional evolution. The Constitution is “… replete with asterisks to sections of the Constitution that are now obsolete or superseded. They are still in there, but they do not work anymore because subsequent legislation or amendment changed the purpose or made the purpose no longer achievable.”[19]

In fact the Twenty-first Amendment[20] is the only instance which explicitly repeals part of the Constitution. But it is clear that other sections of the Constitution have been rendered moot. For example, Article I, Section 2 states that:

Representatives and direct Taxes shall be apportioned among the several States which may be included within this Union, according to their respective Numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole Number of free Persons, including those bound to Service for a Term of Years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other Persons.[21] While no later provision explicitly crosses out this provision from the Constitution, no one doubts that it is not in effect. The Thirteenth,[22] Fourteenth[23] and Fifteenth[24] Amendments make clear that such distinctions between slave and free, black and white are in absolute conflict with the Constitution.

Further, Philip Schrag, a Professor at Georgetown School of Law, concludes that the proposed voting plan for the few remaining residents of the National Capital Service Area would strictly follow the language of the Twenty-third Amendment.[25] According to Schrag, the Twenty-third Amendment only empowers Congress, not the District.[26] The Amendment provides the District with the power to appoint electors “in such manner as the Congress may direct,” and allows Congress to “enforce [the] article by appropriate legislation.”[27] Therefore, if Congress decides that the residents of the National Capital Service Area must vote as residents in New Columbia in order to receive their constitutional right to representation in the Electoral College, then Congress may pass this legislation without fear of violating the Constitution.[28] The Twenty-third Amendment demands that Congress provides District residents with representation in the Electoral College, and Congress will provide that representation in the manner appropriate for the National Capital Service Area.

Thus while the Twenty-third Amendment was the vehicle chosen to provide District residents with representation in the Electoral College, it should not be implied that all other routes to enfranchisement have been foreclosed. Neither the language, nor the purpose of the Twenty-third Amendment in any way conflicts with the pursuit of statehood by the residents of the District of Columbia and so we should not create a controversy where one does not exist. "Give us be free"!

[1] U.S. Const. amend. XXIII. (“Section 1. The District constituting the seat of Government of the United States shall appoint in such manner as the Congress may direct: A number of electors of President and Vice President equal to the whole number of Senators and Representatives in Congress to which the District would be entitled if it were a State, but in no event more than the least populous State; they shall be in addition to those appointed by the States, but they shall be considered, for the purposes of the election of President and Vice President, to be electors appointed by a State; and they shall meet in the District and perform such duties as provided by the twelfth article of amendment. Section 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”).

[2] The District of Columbia House Voting Rights Act of 2009: Hearing on H.R.157 Before the Subcomm. on the Constitution, Civil Rights, and Civil Liberties, of the H. Comm. On the Judiciary (2009) (Statement of Professor Viet D. Dinh).

[3] Adam H. Kurland, Partisan Rhetoric, Constitutional Reality, and Political Responsibility: The Troubling Constitutional Consequences of Achieving D.C. Statehood by Simple Legislation, 60 Geo. L. Rev. 475, 486 (1992).

[4] The passage of the Twenty-third Amendment in 1961 granted Congress the authority to direct the appointment of electors to the Electoral College in the District of Columbia. This authority allows District residents to participate in elections for President and Vice-President. Although valuable, the Twenty-Third Amendment fails to endow District residents with all the rights of citizenship. District residents still cannot vote for Senators, cannot vote for Representatives (with the exception of one non-voting delegate), and cannot be accorded with more electors than the least populous state. The Twenty-third Amendment might narrow the divide between people living in the District and people living elsewhere in the United States, but full statehood for D.C. remains the best option for eliminating that divide.

[5] Dinh, supra note 177.

[6] U.S. Const. art. I, § 8, cl. 18.

[7] U.S. Const. art. II, § 1, cl. 4.

[8] The distinctions between what Congress can do for a district as opposed to a state all assumes that the logic of Adams remains the controlling precedent. Were the Court to reverse its position consider the District of Columbia a state for purposes of representation in Congress it would change the nature of this argument and render much of it moot as the District would then have many of the rights and authorities that come with statehood, all that would remain denied would be home rule. Adams v. Clinton, 90 F. Supp. 2d 35, 72 (D.D.C. 2000) (per curiam), aff’d, 531 U.S. 940 (2000).

[9] Dinh, supra note 177.

[10] U.S. Const. art. IV, § 3.

[11] Dinh, supra note 177.

[12] Kurland, supra note 178, at 3.

[13] H.Rep. No. 100-1 (1987), Stephen Salzburg response at 25.

[14] See Kurland, supra note 178, at 5.

[15] See Raven-Hansen, supra note 130, at 16.

[16] U.S. Const. amend. XXIII.

[17] See Constitution for the State of New Columbia s 1110, 1 D.C. Code Ann. 117, 177 (Supp. 1990).

[18] See Raven-Hansen, supra note 130, at 16.

[19] See Raven-Hansen, supra note 130. Examples of this are U.S. Const. art. 1 § 9; U.S. Const. art. 2, §1; U.S. Const. art. 4; U.S. Const. art. 5; and U.S. Const, amend. XII.

[20] U.S. Const. amend. XXI.

[21] U.S. Const. art. 1 § 2.

[22] U.S. Const. amend. XIII.

[23] U.S. Const. amend. XIV.

[24] U.S. Const. amend. XV.

[25] Philip G. Schrag, The Future of District of Columbia Home Rule, 39 Cath. U. L. Rev. 348, 349 (1990).

[26] See 106 Cong. Rec. 12, 561 (1960) (statement of Rep. Whitener).

[27] U.S. Const. amend. XXIII.

[28] Schrag, supra note 200, at 348-49.