DC Statehood Advocates Battle On

The writer is from France and captured her thoughts on D.C. Statehood while spending time as an intern for Street Sense.*

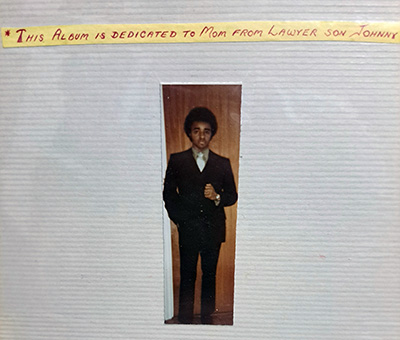

Attorney Johnny Barnes is sitting on the red velvet armchair under the large chandelier in the middle of one of Washington Court Hotel’s ballrooms. The place is filling up little by little.

Attorney Johnny Barnes is sitting on the red velvet armchair under the large chandelier in the middle of one of Washington Court Hotel’s ballrooms. The place is filling up little by little.

“I am not willing to wait,” starts Barnes, the self-described “People’s Lawyer.” He encourages the crowd to take up the chant.

On a sunny morning, members of diverse organizations are gathering for the tenth annual DC Statehood Summit. It’s the latest rally in a long fight. Attendees are united in their desire to transform a large part of the District into the nation’s 51st state. They point out that District residents pay federal taxes and fight in die in the nation’s wars yet they lack a voting representative in Congress.

There is no end in sight for their battle, yet they refuse to give up.

Opponents of statehood for the District argue that the Constitution provides for a federally controlled seat of government and that Congress has no authority to change it.

“That would make the federal government dependent on an independent state, New Columbia, for everything from electrical power to water, sewers, snow removal, police and fire protection, and so much else that today is part of an integrated jurisdiction under the ultimate authority of Congress,” notes Roger Pilon of the libertarian Cato Institute, who testified at a recent Congressional hearing on DC Statehood, the first to be convened in two decades.

Republicans fear that granting statehood to the staunchly Democratic District would give the Democrats more power in Congress, with two more Senate seats and a vote in the House of Representatives.

“Rather than do what is right, the House of Representatives does what is political, they try to tell us how to spend our money,” Barnes contends.

Currently, the 650,000 taxpaying residents of the District of Columbia do not have a voice for how their own money will be spent, because the entire budget has to be ratified by Congress.

“We leave about $2.6 billion on the table that we can’t get, revenue forgone, because we are not a state. This $2.6 billion is one-fifth of our budget: we can put more money in public safety, put more money in education, fix the schools and hire more teachers, we can reduce the taxes with all the money, we can put more money for affordable housing, so the homeless people might have some place to go. We lose that money because we are not a state,” explains Barnes.

According to the advocates of statehood, District residents are relegated to second-class citizenship: they bear all the burdens of the citizens, but do not share the same rights, even with a larger population than either Vermont or Wyoming. They emphasize the fact that city officials are “forced to send every piece of legislation to Congress,” according to Mayor Vincent Gray.

Standing on the ballroom’s platform, Barnes addresses his audience with a strong voice.

“All over the world, the people who live in the capital participate in the government,“ says Barnes. “The United States is alone in the world communities. It is a simple case of democracy denied.”

In 1801, the Congress passed the District of Columbia Organic Act which established a new federal district under the exclusive jurisdiction of the Congress. Since the District was no longer part of any state, its residents lost voting representation in the Congress. Statehood fighters claim that from that day, the people of Washington lost their sovereignty and their democratic rights.

“Too many people have passed away without having the right to vote,” says Barnes.

Hopes were rekindled for statehood when President Barack Obama was elected and chose to display the District’s famous protest license plates “taxation without representation” on his presidential limousines.

They dwindled again after Repblicans retook the House halfway through Obama’s first term. Still the debate over DC statehood resurfaced September 15 when US Senator Tom Carper (D-Del.) held the first Congressional hearing on the issue since 1993.

The bill he introduced, S 132, the “New Columbia Admission Act” would reduce the federal District of Columbia to an enclave of land including the National Mall, the White House, the Capitol, the Supreme Court and the Kennedy Center while the remainder of the city would become the country’s 51st state, with full voting rights in Congress. The proposition has 18 co-sponsors in the Senate. Carper has said he hopes his bill will “restart the conversation” about the injustice suffered by District residents. Though political observers have given the legislation no chance of passage, advocates of statehood are hailing it as a step forward.

“The residents do not believe that we can do anything about it, they accept to live like that. A lot of people do not understand what statehood really is, that’s why they do not do anything and accept the stateless” says Barnes.

While some District residents believe they have true representation in the House of Representatives, Eleanor Holmes Norton is actually considered a delegate and cannot vote on legislation when it comes to the House floor. District residents also lack representation in the US Senate.

“People do not care about statehood due to lack of information, people think that things are the way they are,” notes DC resident Joan Shipps. “Congress is always interfering in our local business,” adds the young mother, who says she wants to raise her daughter in a state where she will have the same rights as any other Americans.

Shipps recalls her own frustration about not having her own member of Congress to fight against HR 7, the legislation that aims to restrict abortion access for women around the country: “With no voting representation in Congress, DC could only send our non-voting delegate, Rep. Eleanor Holmes Norton, to advocate against HR 7 on our city’s behalf”.

Barnes says he plans to file a lawsuit in federal court, seeking to block the planned move of the Federal Bureau of Investigation out of the District as well as the return of the other federal agencies. Indeed, at the time of its creation, Congress made a compact with the residents of the District of Columbia not to remove any federal agency headquarters from Washington, in exchange of the surrendering of certain voting and sovereignty rights. DC statehood defendants note that bargain is not respected anymore and want to restore the rights to people of Washington by the only way: statehood.

“I believe it will work, the court is supposed to follow the law, to interpret the law, without being on anybody’s side,” explains Barnes.

Indeed, according to the New Columbia Admission Act, the Mayor of the District of Columbia must propose adoption of a State Constitution. Congress just needs to approve the bill by a simple majority and the President to sign the bill.

Charles Moreland, the District of Columbia shadow US representative between 1991 and 1995 illustrates this hard battle to the audience: “Congress is the father of the District; statehood is the emancipation of a father.”